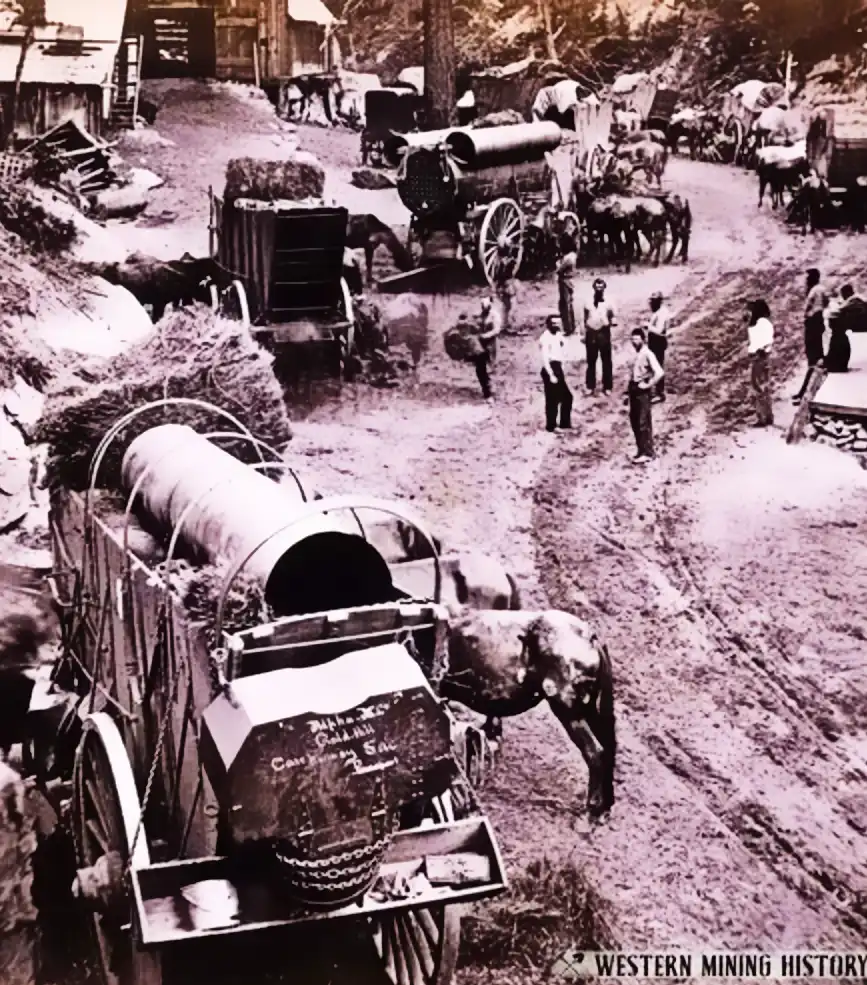

PLACERVILLE, Calif. — An 1860s photograph titled “Feeding the Teams. Scene on the Placerville Route” freezes a moment that once defined daily life in El Dorado County: weary freight wagons halted along the mountain road, horses and mules eating, men resting briefly before pushing on toward Nevada’s booming Comstock Lode.

The image captures more than a pause for livestock. It documents Placerville’s pivotal role in one of the West’s most consequential mining rushes—the Comstock Silver Rush, discovered in 1859 near present-day Virginia City, Nevada. That strike unleashed the first major silver boom in U.S. history, and Placerville became one of its most important supply gateways.

By the early 1860s, Placerville—already seasoned by the California Gold Rush—sat at the western end of a trans-Sierra lifeline. Freight teams hauled food, timber, machinery, coal, clothing and mail eastward to the Comstock mines, returning with bullion, cash and news. The Placerville Route, including the steep Georgetown Divide and high Sierra passes, was among the most heavily traveled wagon roads in the region.

The work was punishing. Teamsters drove six-, eight- and sometimes ten-horse wagons, often hauling several tons at a time. Roads were little more than graded dirt, rutted by iron-rimmed wheels in summer and swallowed by mud in spring. In winter, snow could stack higher than the wagons themselves, forcing crews to shovel, chain wheels or abandon loads altogether.

“Snow, mud and alkali dust made freighting a trade that selected for endurance,”

said historian David Schrepfer, former director of the El Dorado County Historical Museum.

“Placerville’s teamsters were professionals in hardship. They had to be.”

Animals were as critical as the men. Horses and mules required constant feeding and care, which explains scenes like the one captured in the photograph—grain sacks opened, harnesses loosened, steam rising from flanks in cold mountain air. A single injured or exhausted animal could halt an entire outfit.

Mark Twain, who briefly worked as a reporter in Virginia City during the Comstock years, famously wrote of the region’s severity:

“The colder the winter, the hotter the silver fever burned.”

His observation underscored a truth well known along the Placerville Route—fortune favored those who endured.

Placerville benefited economically from this relentless traffic. Blacksmiths, feed stores, stables, hotels and warehouses flourished. The town became a logistics center, not just a mining camp, helping it survive long after nearby gold claims played out. At the same time, the trail hardened its people. Accidents were common, profits uncertain, and competition fierce. Success depended on grit, experience and an acceptance of risk.

By the late 1860s and 1870s, improved roads and eventually rail lines began to eclipse wagon freighting. Yet the legacy of that era remains embedded in Placerville’s identity—a community shaped by movement, muscle and resolve.

The photograph endures as quiet evidence of that past: men and animals bound together by necessity, paused briefly on a rugged road, feeding up before facing the Sierra once more.