"Pony Bob” Haslam

The Last Ride of Pony Bob Haslam

As told from Jackass Saloon, Old Placerville — Spring 1860

By the time spring crept over the Sierra and the pines whispered of snowmelt in their roots, men in Placerville spoke in hushed awe of a rider named Pony Bob Haslam.

He weren’t from these parts at all — born in the foggy streets of London in the year of our Lord 1840 — but by the time he’d hit his twentieth year, he’d taken up the saddle in Salt Lake Territory, worked a ranch and carried dispatches for the government like a man born to his horse.

They called him “Pony Bob,” and by God, he’d earned it.

Word came down along the trail that spring of ’60 that the Paiute had taken to the warpath and stations lay empty where riders once changed mounts. Fear ran thick as dust in a summer gale. Yet Pony Bob, riding for the Pony Express, did not flinch.

He’d left Friday’s Station early one May morn with a mochila full of mail, planning his usual seventy-five mile run to Buckland’s Station. But when he pulled up at Buckland and dismounted, eager for a fresh mount, the relief rider flat refused to take the mail — cowed by rumors of Indians burning stations and stalking riders.

Pony Bob spat in the dust, reined up his mount, and said, “‘Tis no business of mine to shirk.” Within minutes he was back in the saddle, riding on through empty stations, the sun burning high and his horse’s breath coming in steamy gusts.

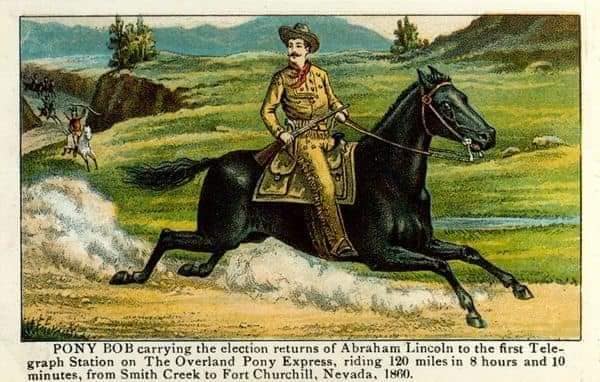

From Carson River to Carson Sink, Sand Springs to Cold Springs, Bob rode on. Water was scarce. The miles stretched ever onward, dusty and unkind. Yet he rode. By the time he handed off the mail at Smith’s Creek, near four-score miles beyond his layover, he had covered an unbroken 190 miles without so much as a ten minute rest.

After a nine-hour rest — because even the fiercest must sleep — Pony Bob mounted again, this time to carry the westbound mail. At Cold Springs he found the station burned, the keeper slain, all stock gone. Unmoved, he rode through gathering darkness, through ringed bands of warriors and past danger unseen, straight as though guided by Providence itself.

By the time he reached Buckland’s again, and finally rode home to Friday’s Station, the ledger read some 380 miles in fewer than two days — the longest journey any Pony Express rider ever laid hoof to ground.

In later years, Bob would tell folks in Salt Lake and Chicago about his rides — about the thunder of hooves and the bite of arrowheads — and folks would pay good coin to hear him. He worked for Wells Fargo, scouted for the Army, even rode with his old friend Buffalo Bill Cody on peaceful missions; yet none stirred the blood of listeners like his tale of that spring when the West itself seemed set on fire.

By the time he drew his last breath in Chicago’s winter cold of 1912, newspapers across the land remembered him as a man who knew no fear — a horseman unmatched, a scout unsurpassed, and the very spirit of the frontier writ large upon his soul.

And old timers in Placerville raise their mugs yet, to Pony Bob — the rider whose name outran the wind.