The sun rode high like a hard-eyed sentinel, its heat pressing down on our backs as if testing our resolve. The humidity was low, the dust relentless, and the air carried that unmistakable Sierra perfume—manzanita sap, insect drone, and the sharp, mocking screech of valley jays that seemed to take pleasure in reminding newcomers exactly how far they were from comfort. We had been pushing forward since dawn, driven by equal parts desperation and the promise of gold, when at last—just as dusk bled purple across the sky—we reached the crest of a pine-clad ridge.

Edgar Allan had written of Eldorado, and as I paused there, lungs heaving, I couldn’t help but murmur the line that rose naturally to my lips: “Over the mountains of the moon, down the valley of the shadow…” Poe knew shadows all too well, and as we stared into the valley below, I realized we were about to walk straight into our own.

Because there, basking in the dying crimson of a sun surrendering to night, lay Hangtown.

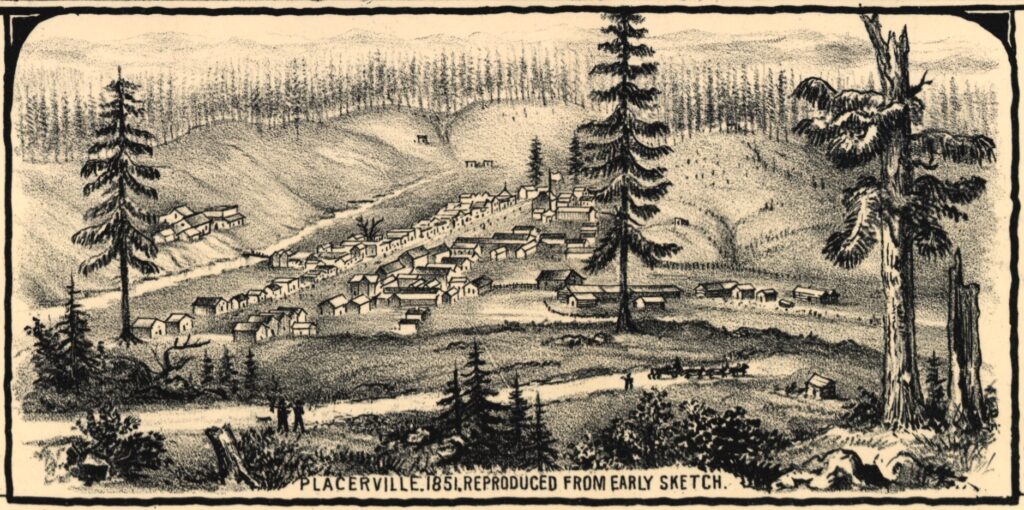

It did not glitter like a city of promise. It squatted. A tortured little creek—thin, stubborn, and angry—wound its way through a jagged series of ravines, each lined with somber pines leaning inward as if whispering warnings to one another. And along that trembling thread of water, clinging to its banks like survivors of a storm-tossed wreck, sprawled several dozen shake-roofed shanties. They reminded me of the Irish quarter back home, rough as a rasp and twice as unforgiving.

Log cabins hunched between them like brooding giants, and beyond those—spreading toward Main Street—rose a chaotic wilderness of tents. Hundreds of them, glowing from within as lamplight and candlelight flickered against thin canvas walls. Oak-scented smoke drifted on the sluggish air, thick enough to sting the eyes. The whole hollow shimmered and twinkled, not unlike a fairy ring—if the fairies had sharp knives and short tempers.

Bursts of rowdy laughter shot upward at intervals, competing with the distant clatter of tin cups and the muted groan of someone clearly losing at cards. From a massive canvas-walled structure near the center of town, a pair of mismatched fiddles scratched out a trembling rendition of “Little Annie Laurie,” the notes wobbling like they feared being caught out after dark.

We descended with caution, each step downward dimming the last of the daylight and deepening the shadows pooling between structures. When we finally reached Main Street, the ground beneath our boots felt beaten, trampled, and somehow… expectant.

A large open space spread before the crowded music tent—the clear hub of Hangtown’s beating, feverish heart. False-front buildings lined both sides of the street, their façades tall but their shoulders sagging, like men trying to seem bigger than they were. The street sloped gently westward, widening as it approached a long barricade of canvas-covered shops. Lamps burned low along their edges, silhouettes flitting behind them like restless spirits.

At the east end of the row loomed a bell tower—tall, skeletal, and ominous. It was the tallest structure in town, though not necessarily the most imposing. Hangtown had a reputation, after all. A bell wasn’t the only thing that had been hoisted here.

Westward, Main Street funneled travelers into a gauntlet of saloons—dimly lit, tightly packed, and already loud enough to suggest fists would soon follow words. Center Street split off toward the creek, where barns and stables perched at precarious angles, as if contemplating a tumble into the ravine below.

And as we paused there, taking in the noise, the glow, the tension simmering under every cheerful shout, a realization crawled cold and insistent up my spine:

Hangtown wasn’t just a town.

It was a test.

And not everyone who arrived would survive it.