Tech Sanderson-LLNL

Cris Alarcon

Surreal turns Real

In 1983, my older brother Scott—ten years ahead of me in age and experience—approached a new venture: he had already completed his union apprenticeship as a Journeyman Lather and Plasterer, specializing in drywall and suspended ceilings. Together, we founded American Interior Specialties (AIS) as equal partners. I brought my newly minted business education; Scott brought trade expertise. Our “warehouse” was nothing more than our backyard garage in San Jose.

To learn best practices, I secured a union job in commercial construction. We began with residential remodels, graduated to commercial jobs—among them an IBM assembly plant near Campbell—and even tackled a high‑end housing development in Livermore. In those days, home computers were just beginning to surface, and we installed pre-wired Category‑5 Ethernet wall ports in luxury homes.

When Business Curved into the Obscene

As Scott eased away from physical labor into office-based management, he began pronouncing everyday terms with odd affectations—referring to “columns” as “Col‑Lee‑Ums”—and gravitated toward computers. He confided he’d launched a file‑sharing venture—not for drywall specs or architectural diagrams—but for adult pornography, distributing it via membership. He described learning from “friends” now to set up FTP and SSH for remote access to servers.

As this “dirty picture” business gained momentum, our drywall contracts suffered. I felt our partnership fray and our friendship fail. Without interest in porn, I focused on college, studying Business and Physics in Southern California. By then I’d toured Fermilab’s linear particle accelerator near Chicago and understood the research underway at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory [LLL]—a DOE lab operated by UC Berkeley.

A Christmas Reunion and a Surreal Revelation

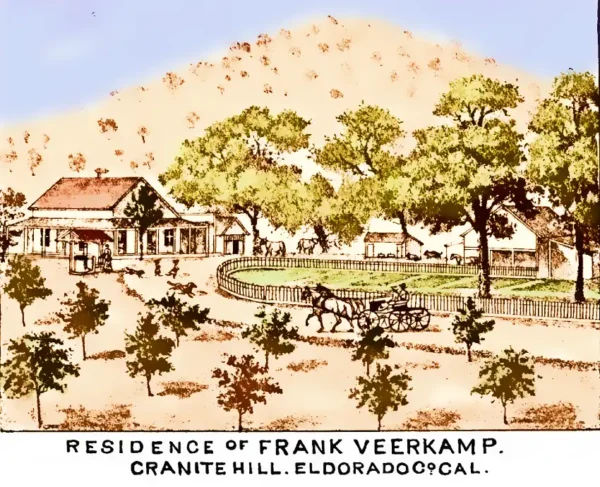

In December 1992, I received a call from my mother inviting me to spend Christmas with her, Scott, and his family in Livermore at his new place in Livermore. My fiancée Sherri and I drove up from Walnut; I even got lost entering Livermore until a helpful LPD officer guided us to Scott’s house. We pulled up to a modest rental home and a new truck—he was supporting several kids so it’s clear Scott’s side business was doing well.

Yet there was no warm greeting. Scott abruptly said, “Come—gotta show you my new warehouse,” and hustled me into his truck’s passenger seat. He launched into a technical monologue: computer storage was expensive, ISP transfer speeds slow, but he’d found a genius workaround—tap into LLNL’s internet “trunk line” by drilling down to fiber cables, and host his porn on the lab’s nearly unlimited storage. He had supposedly recruited lab friends to to do the programing at LLNL and he would drill a shaft into the conduit running beneath a rented warehouse unit at 2370 Research Dr.

He took me to his unit and excitedly jumped on the asphalt floor, claiming the lab’s mainline was right underneath. I feigned enthusiasm while mentally rejecting his theory—the lab’s classified systems were well air-gapped, I knew—and chalked it up to delusion.

Truth Became Stranger Than Fiction

Fast-forward to July 1994, when Adam Bauman of the Los Angeles Times broke the story: LLNL computers were used to store and distribute hard-core pornography, in what was described as “among the most serious breaches of computer security” at the lab washingtonpost.com+3latimes.com+3washingtonpost.com+3. The lab shut down the offending server after it was accessed by the reporter . At least one employee was involved, but the lab claimed classified systems remained secure behind air gaps latimes.com.

By August 18, 1994, felony charges were unveiled against technician William Allen Danforth—alleged to have stored 90,000 pornographic images on lab tapes and shared them online upi.com+2latimes.com+2washingtonpost.com+2. Another employee, Michael William Lazzarini, faced minor charges. More than 50 GB of pornographic content was recovered, some including child imagery latimes.com+2latimes.com+2washingtonpost.com+2. The lab spent over $13,000 investigating and placed Danforth on investigatory leave; he resigned on August 15, 1994 latimes.com.

A spokesperson reported that as many as 20 collaborators inside and outside the lab were involved washingtonpost.com+2latimes.com+2latimes.com+2. The assistant district attorney noted most images were adult pornography, but about 0.04 % were child-related latimes.com+1washingtonpost.com+1. Danforth faced up to three years in prison and $10,000 in fines per count latimes.com+1washingtonpost.com+1.

Looking Back with Authorial Clarity

I realize now that night at the warehouse was not mere fantasy—it foreshadowed a real event of national significance. Scott’s audacious plan echoed the audacity of Danforth’s breach—piggybacking illicit content on institutional infrastructure. Fortunately, when the scandal broke, I was far away in college, untainted by its fallout.

This episode remains a stark contrast between my own path—business and science rooted in integrity—and my brother’s descent into ethically dubious enterprise. It also highlights a pivotal moment in the evolution of computer security: a cautionary tale showing that even elite research labs are vulnerable when oversight lapses.

Summary:

-

1983: We launched AIS together, thriving commercial construction.

- 1984: Cris left the construction business in San Jose and Moved to SoCal to attend college.

-

1992: Scott reveals his porn‑hosting scheme built on LLNL’s lines—nonsensical at the time.

-

1994: The scandal erupts in headlines: LLNL exploited for massive porn storage—90,000 images, 50 GB+ recovered. Charges filed; lab reforms follow.

- 1994: My brother suddenly uprooted from California and moved to Commerce, GA 30530